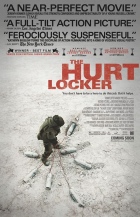

The Hurt Locker

|  Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker is a visceral, heart-pounding experience that is easily the best film yet to made about the current war in Iraq and also one of the best war films of the past decade. As a cinematic subject, Iraq has been a bust, producing generally stodgy, well-meaning films of bloated self-importance that have not registered at all with audiences who are weary of the themes and images from 24-hour news. One of the reasons The Hurt Locker clicks where others have failed is that it does not try to be “about” the war in Iraq; rather, it simply uses the war as a background setting for a fascinating character study about the potentially addictive thrills of mortal danger. Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker is a visceral, heart-pounding experience that is easily the best film yet to made about the current war in Iraq and also one of the best war films of the past decade. As a cinematic subject, Iraq has been a bust, producing generally stodgy, well-meaning films of bloated self-importance that have not registered at all with audiences who are weary of the themes and images from 24-hour news. One of the reasons The Hurt Locker clicks where others have failed is that it does not try to be “about” the war in Iraq; rather, it simply uses the war as a background setting for a fascinating character study about the potentially addictive thrills of mortal danger.The film opens with a blunt statement by New York Times war correspondent Chris Hedges that “war is a drug,” something that will not immediately register with most people who imagine war to be a horrific experience to be avoided at all costs. Yet, by the end of the film Bigelow and screenwriter Mark Boal, who spent time embedded with a U.S. Army Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) unit in Iraq, have made clear just how addictive the danger of warfare can be for certain personalities, which produces a double-edged sword: On a practical level, such people are clearly indispensible for a military operation, yet there is tragedy in the fact that they can only feel alive when their lives are literally on the line. When the film ends with the image of someone purposefully returning to the war zone because he is incapable of breathing in the civilian world, it is presented with an air of triumph, yet there is an underlying irony that rips your heart. The primary character is Staff Sergeant William James (Jeremy Renner), who is brought in to head a bomb disposal unit in Bagdad after the previous commanding officer is killed in an explosion, an event that opens the film and establishes both Bigelow’s supreme command of the tense material and the stakes of the narrative: Anyone at any moment can be killed by the force of a homemade explosion. For James, defusing bombs is his life. He has been doing it for so long and so successfully that his skills in figuring out a bomb’s construction and how to dismantle it under the pressure of a ticking clock have come to define him. He is what he does, which is reflected in the fact that he keeps a box under his bed filled with souvenir parts from those special bombs that came particularly close to killing him. The other members of James’s team are Sergeant J.T. Sanborn (Anthony Mackie), a no-nonsense professional who bristles at James’s often daredevil attitude toward his work and blatant disregard of the procedures designed to keep them all safe, and Specialist Owen Eldridge (Brian Geraghty), who is young and frequently frightened and thus reflects how most of us would probably respond to the situations in which the characters are constantly placed. Boal’s narrative structure is built primarily around various episodes involving the team being called in to diffuse bombs, most of which are in broad daylight in a very public place (usually on the side of a street or in a parked car or, in the film’s most horrific sequence, strapped to a man’s chest with padlocks). Disguised beneath piles of garbage or buried just beneath the sand, these homemade contraptions are particularly lethal because they are aimed at everyone and no one. If one were to explode, it would take out anyone and anything within a certain radius, which means that James must go in alone (civilians are cleared out and the perimeter around the bomb is maintained by Sanborn and Eldridge). Thus, the film’s most oft-repeated image is one of James walking unaccompanied into a strangely deserted space, in the center of which is a device designed to kill him that he must dismantle--an apt visual metaphor for his emotional and personal isolation from those around him, both near and far (he has a wife and young child at home, but you never get the sense that they are close in his mind). All the time he is also being watched by Iraqi citizens, any one of whom may very well be the bomb’s creator. For Bigelow, who has worked consistently for the past two decades as a rare female director making films that are usually considered the sole domain of men, The Hurt Locker is a particular triumph, especially since she has been largely inactive since 2002 when her expensive Cold War thriller K-19: The Widowmaker, a generally good movie that had the misfortune of miscasting Harrison Ford as a Soviet submarine commander, was a summer box-office dud. Bigelow is at her best when depicting characters who are defined by their extremes, whether it be Patrick Swayze’s spiritually enlightened bank robber in Point Break (1991) or the various characters hooked on “jacking in” to other people’s recorded experiences in Strange Days (1995). She is an expert craftswoman who knows how to draw out tension to the breaking point, and her skills are put to great use in The Hurt Locker, which is so tautly constructed in its best moments that it holds you spellbound and very nearly breathless; it gets you ramped up time and time again, with each subsequent episode building on the danger and release of the previous one. The film’s genius and the source of its raw emotional power is the way it draws you into the world of its characters and holds you there, helping you to understand what otherwise would be inconceivable, which is also what makes it so fundamentally humane, a quintessential trait of great war cinema and one that is too frequently lacking in the bloated excess of the summer movie marketplace. Copyright ©2009 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Summit Entertainment |

Overall Rating:

(4)

(4)