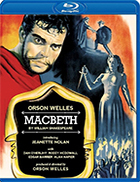

Macbeth (1948)

|  Although often considered a relatively minor film in his multi-decade oeuvre, Orson Welles’s Macbeth is one of his most fascinating film experiments and a bridge between his brief, tumultuous Hollywood career that began with the extraordinary Citizen Kane (1941) and the subsequent decades of exile as an independent filmmaker in Europe. Welles had been adapting Shakespeare since he was a schoolboy (when he was 16 he produced, directed, and starred in a compilation of Shakespeare’s historical plays called Winter of Discontent at his boarding school), and it was his daring 1936 Federal Theatre Project staging of Macbeth set in Haiti with an all-black cast that helped garner him sustained attention at the ripe young age of 20. Thus, it is not surprising that, when given the opportunity, he would translate Shakespeare to the screen in his own unique way and start with the moody, violent Macbeth (he would go on to direct an adaptation of Othello in 1951, and in 1965 he made Chimes at Midnight, a compilation of elements from Henry IV, Part 1, Henry IV, Part 2, and Henry V). In adapting the play himself, Welles condensed it considerably, streamlining much of its narrative and characterological complexity and cutting down or otherwise eliminating some of the lengthier monologues (as numerous critics have noted, he did not feel any need to remain slavishly faithful to the particulars of Shakespeare’s original text). Instead, he focused on blunt psychology, melodramatic emotions, and easily recognizable motivations; this had always been his tendency with Shakespeare, although after the contrived and confusing plot machinations of his previous film, The Lady From Shanghai (1947), he may have felt even more motivation to keep things simple and direct. His version of Macbeth is decidedly more primitive than audiences were accustomed to, and as a result, the story of the titular Scottish nobleman (played by Welles) murdering King Duncan (Erskine Sanford) in a bid for absolute power bears little in the way of nuance, but loses none of its underlying dramatic power. The world in which Welles stages the story is barely even civilized, so the lurches into violence and murder don’t feel like betrayals of a well-established social order, but rather the bubbling up of the most rudimentary and animalistic of emotions from just beneath a thin veneer of civility. The opening scene with the witches, who here are recast as Druid priestesses dabbling in what looks like some version of voodoo, ranks as one of Welles’s best and most haunting sequences; it has a grisly, earthy, unnerving quality that stays with you for the rest of the film, especially in juxtaposition to the Holy Father (Alan Napier), a character Welles created to represent nascent European Christianity. Welles’s Macbeth is a brute, and you can sense the relish with which he plays the character’s violence, ambition, and ultimate arrogance. His chemistry with Jeanette Nolan, who plays Lady Macbeth, isn’t always as ripe as it could be, but they still make a fairly dynamic pair in their scheming. In addition to staging Macbeth in 1936, Welles had also performed it on the radio with Agnes Moorehead, and in 1947 he staged it again as part of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. It was that staging that became the basis for his film version, which helped the production move in quick fashion since the staging essentially functioned as a rehearsal and he kept the same basic production design, which took the play away from the Renaissance trappings that Welles disliked and instead located it deep within primitive medievalism. Although shot almost entirely on soundstages with a relatively meager budget for Republic Pictures, a small upstart studio, Welles’s Macbeth has an intense, primeval visual grandeur that makes its base emotions of greed, hatred, and vengeance feel all the more elemental. The production design makes it appear as if Macbeth’s castle has been roughly carved out of the side of a craggy mountain, and the cinematography by John L. Russell (who would go on to shoot Hitchcock’s Psycho) is a marvel of expressionist traits—the canted angles, deep shadows, oblique lines, and deep space staging all feel like they have been ripped directly from a German Expressionist film from the ’20s, which only adds to the overall grotesquerie. Unfortunately, like so many of Welles’s films of this era, Macbeth was seen by only a few people in its original version, as the studio worried that it was too long and that the thick Scottish accents would make it difficult for audiences to follow the story. After Welles’s version was savage by critics at Life magazine and The Hollywood Reporter, Republic insisted it be withdrawn and reworked prior to general release. To appease the executives, Welles worked to cut the film down, reducing it from 107 minutes to a mere 89 minutes, and redubbed substantial portions of the dialogue. Unfortunately, none of the tampering changed the perception that the film was an outright disaster, although, not surprisingly, critics and filmmakers in Europe appreciated Welles’s daring and artistic license, which too many others viewed as a weakness (especially in comparison to Laurence Olivier’s much more conventional and universally praised 1947 film version of Hamlet). For three decades Welles’s original version was all but lost, but it has since been discovered and restored, bringing back to light a film that had an unfortunately deleterious effect on his career, but can now be seen and appreciated as a unique, daring take on a familiar text that rendered it new and strange. In other words, we see that, once again, Welles was working ahead of the curve and paid the price for it.

Copyright © 2024 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Kino Lorber | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3.5)

(3.5)