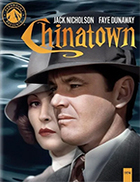

Chinatown (4K UHD)

|  Roman Polanski’s Chinatown is one of the great masterworks of ’70s American cinema and an apex of the decade’s obsession with genre revisionism. Along with Coppola’s The Godfather (1972), Altman’s Nashville (1975), and Spielberg’s Jaws (1975), which reimagined the gangster film, the musical, and the monster movie, respectively, Chinatown helped usher in a new era of gutsy American cinema in which the genres of Hollywood’s golden age were rewritten with new rules, heightened aesthetic intensity, and a sharper, if frequently more despondent, tone that no longer had to play by the dictates of the industry’s Production Code. Robert Towne’s screenplay, still hailed as one of the finest ever written and a model that aspiring screenwriters study and attempt to emulate, pays loving homage to, while also slyly undercutting, many of the dictates of the hard-boiled detective story, which was forged by pulp writers like Dashiell Hammett and Mickey Spillane and then given expressive cinematic life in ’40s and ’50s film noir by filmmakers such as John Huston, Jules Dassin, Fritz Lang, Robert Siodmak, and Orson Welles. Set in Los Angeles in the late 1930s, Chinatown was one of the first modern films to consciously evoke the bygone era of film noir. Even though it was shot in color, John Alonzo’s sepia cinematography, which frequently resembles old, faded postcards, has the same visual effect as black-and-white while also emphasizing the arid environment in a way that purely monochromatic images never could (which is absolutely crucial for a film that centers on the centrality of water in the power struggle over the development of Los Angeles). One of the means by which Chinatown deviates sharply from the films that inspired it is the protagonist. Unlike Humphrey Bogart’s Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon (1941), which is generally considered the first true film noir, Jack Nicholson’s private detective J.J. Gittes is not a primal masculine archetype, but rather a complicated and at times unintentionally absurd protagonist whose sense of control is highly illusory. The film immediately establishes his less-than-ideal persona via his work snapping pictures of adulterous spouses, a lowbrow form of detective work that is typically beneath the more admirable private eyes. His dapper sense of style makes him into a vain dandy of sorts, and while he manages to hold his own most of the time, he is also made to play the fool, such as when he insists on telling a bawdy joke in an inappropriate situation. Far from cool and collected, he is simply self-possessed, and much of the film pivots on undercutting his misplaced self-confidence, never so directly (and painfully) than in the scene in which a pint-sized thug (played, not incidentally, by Polanski himself) slices his nostril with a switchblade. The cutting itself causes us to wince, but more importantly it leads directly to the ridiculous image of Nicholson playing the tough detective with a massive white bandage on his nose—in other words, vintage Polanski. Other characters also play into and against expectations. Faye Dunaway’s Evelyn Mulwray, a mysterious woman whose husband (Darrell Zwerling), an engineer with the city’s power and water department, is murdered, provides an endless stream of contradictions and apparent secrets. Her evasiveness and mood swings suggest the manipulations of yet another dangerous femme fatale, but Dunaway’s vulnerability constantly tempts us with the notion that she is the victim, rather than the villain. Outright villainy is instead embodied by Noah Cross, Evenlyn’s father and one of the wealthiest and most powerful men in Los Angeles. Played with insidious gusto by the great John Huston, who directed Bogart in The Maltese Falcon three decades earlier, Noah Cross is one of the cinema’s most unnerving depictions of evil. He is, in every sense, J.J. Gittes’s opposite, not in some simplistic sense of good-versus-evil morality, but rather in the sense that Gittes’s illusion of control is Noah Cross’s reality. In hindsight, we recognize that the narrative momentum in Chinatown moves us inexorably toward the revelation of the depths of Noah Cross’s depravity, which is at once so banal and so horrific that we are left baffled, troubled, and lost. The key line of dialogue in the film is when Cross tells Gittes, “You may think you know what you’re dealing with. But believe me, you don’t,” to which Gittes responds by snickering and saying, “That’s what the district attorney used to tell me in Chinatown.” He thinks he can get to the bottom of the case by exposing Cross and his illegal dealings, but it is that very ambition—which, not incidentally, climaxes in Chinatown, the film’s all-encompassing heart of darkness—that swallows him whole. His intense desire to know is the seed of his own destruction, as well as others around him. Notoriously bleak, yet utterly compelling, Chinatown’s ending (which was a source of great contention between Towne and Polanski and was undecided when production on the film began) is one of the greatest of modern cinema; it is so complete in its depiction of evil triumphant that it demands that we reflect on it philosophically. Like the ending of Rosemary’s Baby (1968), Polanski’s great horror masterpiece, the brute force of its ugly truth is the heart of the film’s artistry, and it sticks with us. Gittes is famously told “Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown” at the end of the film, but we can’t. It is, in a word, unforgettable.

Copyright © 2024 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Paramount Home Entertainment | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(4)

(4)