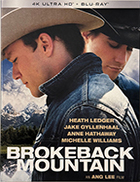

Brokeback Mountain (4K UHD)

|  An Oscar-winning lightning rod in the still raging cultural wars, Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain should be appreciated first and foremost as a heartbreaking romantic epic, a genuinely moving story about repressed desire that transcends any boundaries the various cultural warriors want to impose on it. Both sides have done it a disservice by thinking of it primarily as “that gay cowboy movie,” which downplays its transcendent humanism in favor of political bantering. Based on Pulitzer Prize-winning author Annie Proulx’s 1997 New Yorker short story, Brokeback Mountain begins in 1963 with two poor young ranchers, Jack Twist (Jake Gyllenhaal) and Ennis Del Mar (Heath Ledger), looking for work in a tiny mountain town in Wyoming. They are given a job herding sheep on Brokeback Mountain, a lonely occupation in which they are alone for days at a time, with little to do but fend off coyotes and their own boredom. Given that this is pre-Stonewall and the fact that Jack and Ennis both envision themselves as descendants of prototypical masculine American archetypes working the land, they are largely unaware of any physical and, importantly, emotional desire for each other. Yet, when they first meet, they are clearly cruising each other with stolen glances and awkward posturing, even if they don’t know it. One cold night, when they decide to share a tent, Jack instigates something sexual that Ennis at first rebuffs, then accepts with an almost frightening ferocity that belies his confusion at his own actions. “It’s nobody’s business but our own,” Jack tells him the next day in a moment that seems tender, but is really dark foreshadowing of the fact that their relationship, no matter how intense, will remain closeted for decades. Both men leave their summer on Brokeback Mountain and attempt to steer themselves into lives of “normality,” which means marrying and raising children. Ennis marries his longtime sweetheart, Alma (Michelle Williams), while Jack wanders through the rodeo circuit, eventually falling into the arms of a sexually forthright cowgirl named Lureen (Anne Hathaway), whose family-owned business will provide Jack with a comfortable lifestyle and potential respectability. Yet, neither of them can quite forget the other, and their time together nags in the back of their minds. Finally, after four years they are reunited and immediately pick up where they left off, returning to the fabled Brokeback Mountain, which becomes a physical and symbolic locus of solitude where they can be together in a way they can’t be otherwise. Over the years, they reunite every few months, leaving behind their everyday lives for a few days in each other’s arms. Jack, the more confident of the two, suggests that they get a ranch together and live out their lives as they want, but Ennis is troubled by a childhood memory in which his father took him to see the mutilated corpse of an ostensibly gay rancher who was murdered for his sexuality. Ennis’s fear of fully embracing Jack and, along with it, his own nature overcomes any simplistic notion of a straight/gay divide and becomes instead an all-encompassing paean to every love affair that has been crushed beneath the weight of social convention or family-related propriety. Screenwriters Larry McMurtry and Diana Ossana have worked extensively in the Western genre (McMurtry is the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Lonesome Dove, among many other Western novels, and Ossana has worked exclusively writing Western teleplays with McMurtry, several of which were based on his novels), thus they understand well the conventions of the form, notably the homosocial bonding that, by its very nature, requires the exclusion of women. Some decried Brokeback Mountain for “queering” an ostensibly masculine and unquestionable cornerstone of American mythology, but all one need do is watch the gun comparison sequence in Red River (1948) to see just how easily the latent homosexual connotations of the Western can come to the surface. Director Ang Lee was coming off an uneven few years, in which he followed his international breakthrough martial-arts film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) with the ambitious, but ultimately flawed comic book adaptation Hulk (2003). Returning to the dramatic terrain he had mined so well in his English-language debut The Ice Storm (1997), Lee draws deep from the currents already running through the Western, using Mexican cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto’s exquisitely wrought vistas to suggest transcendence in a world of repression and doubt. Against that backdrop, Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhall give the kind of performances that take a story from a conceit to something that truly gets into your heart. Gyllenhall is the more boyish of the two, full of optimism and therefore more overtly wounded when he runs up against the walls that hold him in. Ledger, in one of his final roles before his untimely death in 2008, appears at first to be stuck in a rut of coarse mumbling, but as the film progresses, we begin to see fine nuances in his downcast eyes and minimalist speech, ranging from a fierce sense of dignity, to an ultimate level of tortured heartbreak. The film as a whole is perhaps a bit too long, with its extended narrative frame never quite falling into a sustainable sense of the passage of time. Yet, any flaws the film may have are more than redeemed by its intrinsic humanity and soulfulness, the kind that is often missing equally from big-budget Hollywood fare and self-consciously quirky indie films. The final scenes of Brokeback Mountain, scored by Argentinean composer Gustavo Santaolalla’s quietly elegiac guitars backed by lush strings, strike deep and stay there, suggesting with the simplest of images that would have made John Ford proud how true love, however thwarted, is simultaneously transcendent and terribly fragile.

Copyright © 2024 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Kino Lorber / Universal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3.5)

(3.5)