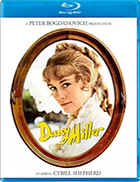

Daisy Miller

|  When Quentin Tarantino published his first book of film criticism, Cinema Speculation, a few years ago, it surprised exactly no one that he focused entirely on American films from the late 1960s and ’70s that he first saw when he was a kid. The movies he wrote about comprised an entirely predictable laundry list of his cinematic inspirations, fascinations, and obsessions: Bullitt (1968), Deliverance (1972), Taxi Driver (1976), The Getaway (1972), Rolling Thunder (1977), Daisy Miller (1974) … Wait—what? Daisy Miller? Yes—buried in the middle of long chapters praising the exhilaration of violence, rough-hewn masculinity, racial tension, celluloid sleaze, vigilantism, and brutal crime is Peter Bogdanovich’s widely panned adaptation of Henry James’s 1878 novella that he produced primarily as a star vehicle for Cybill Shepherd, his then girlfriend. It is the only period film in Tarantino’s book. It is the only one that doesn’t involve a single moment of violence beyond some curtly uttered words. It is the only one centered around a female character. And it is certainly the only one that is rated G. So, what is Daisy Miller doing in the middle of Cinema Speculation? It is clearly a film that Tarantino values, as he describes it as Bogdanovich’s most “underrated” film. And the reason he values it is because he sees that Bogdanovich, despite all the period trappings and other serious accoutrement that goes along with a society drama set in the late 1800s, was making a comedy—for the first half, anyway (Tarantino loves pulling tonal and generic switcheroos). He rightly notes that the film “achieves a rapid-fire pace of overlapping Hawksian comedic rhythm to the dialogue,” which is by far its greatest asset and also the quality that most sets it apart from its source material. (The film is also beautifully shot, certainly the best work ever done by Italian cinematographer Alberto Spagnoli, who otherwise spent most of his two-decade career shooting soft-core sleaze and bad horror.) While Shepherd was roundly (and often cruelly) panned for her performance, which feels much more late-20th-century than late-19th-century, Tarantino argues that the very modernity of her presence is central to the character of Daisy Miller, who refuses to fit into the upright Vicrtorian-era society of American expats living in Europe. Bogdanovich signals this in the very first scene with a lengthy conversation between the film’s nominal protagonist, an American intellectual living abroad named Frederick Winterbourne (Barry Brown), and Randolph C. Miller (James McMurtry), a precocious, buck-toothed ten-year-old who hates Europe and doesn’t mind saying so. (Interestingly, McMurtry is the son of writer Larry McMurtry, whose novel The Last Picture Show Bogdanovich had adapted three years earlier. Brown, on the other hand, was a study in tragedy, as he wrecked his brief career as both an actor and film historian in alcohol and eventual suicide at age 27.) The comical rhythm of their conversation, with Frederick trying to be the good adult and Randolph acting like an outcast from The Bad News Bears, alerts us to the fact that this will not, despite the gauzy location photography and attention to period detail, be a traditional period film. The screenplay by Frederic Raphael, who had recently written Darling (1965) and Far From the Madding Crowd (1967) for John Schlesinger and would later write Eyes Wide Shut (1999) for Stanley Kubrick, stays largely true to the plotting in James’s novella and its focus on the rigidities of high society and the scorn that is heaped on those who dare deviate from its precious rules, which is precisely what Daisy Miller (Cybill Shepherd) does again and again. Whether she is an innocent or a rebel remains tantalizingly vague, as her willfully noncomformist actions—like walking in public with two men by her side—are done with a gleaming smile that feels delightfully intentional and sweetly naive at the same time. I suspect that the reason Shepherd’s performance was panned so widely is because it always feels like a performance; however, that misses the point, as her performativity is central to her character and the overall tone of the film. Everyone is performing because that is what they are expected to do. The problem is that Daisy isn’t performing the way they want her to (nor does her baffled mother, played with sweet humor by Cloris Leachman). The “they,” in this case, are embodied by Mrs. Costello (Mildred Natwick), Frederick’s stuffy aunt, and Mrs. Walker (Eileen Brennan), a brittle woman who polices the behavior of those around her as if the world depends on it. What we see in all of these characters is the way social rituals and priggish behavioral expectations snuff out life and vitality, which Daisy embodies and Bogdanovich underlines by turning her verbosity into quick-timed screwball wit. Shepherd delivers her voluminous dialogue, which Bogdanovich captures primarily in calculated long takes, with casual authority, which is why it is so funny when, after being told Frederick’s full name, she quips, “I can’t say all that.” But, alas, Daisy Miller is not a comedy in substance, only at times in its tone, and sudden, brutal tragedy is waiting around the last corner. The suddenness with which it arrives might be written off as lousy plotting if it didn’t hit so hard and play so well into the film’s larger thematic focus on how ultimately trivial social niceties are. Daisy Miller ended up doing lasting harm to Bogdanovich’s career (one could argue that he never really recovered) and it would take the ’80s television series Moonlighting to turn Cybill Shepherd into a star, but it has been unfairly maligned for too long and deserves a revisit.

Copyright © 2024 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Kino Lorber | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3)

(3)