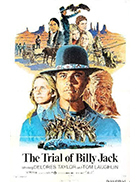

The Trial of Billy Jack

|  Tom Laughlin’s Billy Jack (1971) will always be one of the unlikeliest of success stories in contemporary Hollywood history. Independently produced on a shoestring budget and assembled with a whole lot of belief in its complex and sometimes contradictory mix of pacificism and righteous indignation, it baffled critics and distributors while becoming a major box office hit not once, but twice—first in 1971 when it was released by Warner Bros. and then again in 1973 when Laughlin, who starred in the titular role, co-wrote the screenplay, and directed, sued to get the distribution rights back and then four-walled the film throughout the country, earning even more than in the initial run, making it one of the most financially successful independent films of all time. So, with the massive, two-time success of Billy Jack at the box office, it was no surprise that Laughlin and his wife Delores Taylor, who also co-wrote the original film and had a major starring role, would make a sequel, although no one could have predicted the contours of their magnum opus, The Trial of Billy Jack, which they initially released on over 1,000 screens on its opening weekend, an unheard-of strategy at the time (it set an opening weekend record with $11 million and ended up earning well north of $30 million overall, making it the fifth highest grossing film of 1974, just ahead of The Godfather Part II). Although still credited with pseudonyms, Laughlin, as director, star, and co-writer, and Taylor, as star and co-writer, took advantage of their singular moment, pouring into the film everything but the proverbial kitchen sink. There is something noble in their intentions and dedication, but it comes at the expense of discipline and common sense. Although their concerns about government overreach and the subjugation of minorities and the marginalized still has unfortunate resonance under the new Trump-Musk regime, they pour it on so thick and heavy that even the most dedicated of liberals in the audience will likely wince and squirm a time or two. Flush with cash that allowed them to shoot in ’Scope widescreen, employ more helicopter shots (especially the fabled Monument Valley), work in optical effects and big explosions, choreograph bigger fight scenes, and hire Oscar-winning composer Elmer Bernstein to punch up the music, Laughlin and Taylor took everything that was good and admirable in their previous film and expanded it to the point of pretentious overindulgence. Clocking in at nearly three hours, The Trial of Billy Jack tells roughly the same story as its predecessor—with Laughlin’s near-mythical Billy Jack, a half-Native American Vietnam veteran and Hapkido master working with Taylor’s earnest Jean Roberts to expand their idealistic Freedom School in the Arizona desert—but with more speechifying, more peace pandering, more dewy-eyed sentimentalism, and more of just about everything else that could turn a potentially effective story into a bloated mess. Like the larger budget and fatter script, the stakes in The Trial of Billy Jack are much higher than in its predecessor. Rather than just fighting against bigoted local businessmen and cops, the Freedom School is faced by an enormous web of opposition that extends beyond the locals to bankers, state officials, and even the military and the CIA (it is, if anything a true product of the paranoid post-Watergate era, right up there with The Conversation and The Parallax View, both of which were released the same year). The school begins an investigative journalism program and starts airing exposés on their local television station, which (naturally) irks those whose corruption is being exposed. The film is awash with references to government dirty deeds, with several direct statements about Nixon and Watergate thrown in for good measure, not to mention references to the My Lai and Kent State massacres. More specifically, the film directly indicts governmental use of force against its own citizens. Opening with statistics about the numbers killed and wounded in various conflicts between National Guard troops and protesting college students, the film ends with a vicious bloodbath at the Freedom School that is like all those conflicts rolled into one. Laughlin offers a bone in the form of one Guardsman who has a conscience, but the rest are portrayed as bloodthirsty rednecks just itchin’ to kill ’em some hippies. This, of course, is the primary flaw of the Billy Jack films: They take real-life issues and blow them up so large and exaggerated that it becomes too easy to dismiss them as leftwing paranoia even if you are sympathetic to their perspective. The Trial of Billy Jack has important things to say about a litany of topics, but too much of it gets lost in all the hot air.

Copyright © 2025 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Shout! Factory | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(2)

(2)

This four-disc set includes The Born Losers (1967), Billy Jack (1971), The Trial of Billy Jack (1974), and Billy Jack Goes to Washington (1977).

This four-disc set includes The Born Losers (1967), Billy Jack (1971), The Trial of Billy Jack (1974), and Billy Jack Goes to Washington (1977).