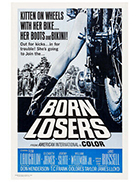

The Born Losers

|  In a 1977 interview with Beverly Walker that was published in Film Comment, actor/filmmaker Tom Laughlin described the moment when he first came up with the idea of what would become his iconic counterculture-vigilante hero Billy Jack: “I was visiting Dody [his then-girlfriend and eventual wife and artistic collaborator, Delores Taylor] in South Dakota; this was about 1957. One day we went to get ice at the other end of town, at the edge of the Rosebud Reservation. I saw people living in tar paper shacks and in abandoned automobiles. Babies slept in trunks. That triggered it and the story was written quickly from incidents told me all over town.” And, while the story that would eventually become the hit film Billy Jack (1971) was written quickly, it was not quickly made. As Laughlin told it, no one wanted to buy the script, so it sat on a shelf for a decade and a half. However, in the mid-1960s, while he and Taylor were running a Montessori school, they read about an incident in Philadelphia in which a Marine veteran broke up a gang rape using a rifle and was sentenced to 18 months in jail while the rapists got off with a minor charge of disturbing the peace. They later heard about another incident in which five teenage girls were raped by members of a motorcycle gang in Monterey, California, none of whom were prosecuted. By combining and fictionalizing these events in a script for what would become The Born Losers, they created a new opportunity to introduce Billy Jack by borrowing the character from the earlier screenplay and dropping him in the middle of the action. At the time, The Born Losers was seen primarily as an early entry in the soon-to-be-popular motorcycle gang exploitation genre. Marlon Brando had already established the archetype in The Wild One (1953), but it took on new urgency in the late 1960s with headlines about the Hell’s Angels and the recognition that many Vietnam veterans who felt like outcasts from mainstream society were taking up with motorcycle gangs. Low-budget movie entrepreneurs saw endless possibilities, with Vietnam vets both fighting against biker gangs, as in The Angry Breed (1968), Satan’s Sadists (1969), and Chrome and Hot Leather (1971), or joining them, as in Angels From Hell (1968). The title for The Born Losers is taken from the name of the film’s Hell’s Angels-like motorcycle gang, which is led by the sadistic Danny (Jeremy Slate) and populated with leering characters bearing names like Gangrene and Crabs. Laughlin’s Billy Jack (wearing a straw cowboy hat instead of the black, flat-brimmed hat with Indian beads that came to define his character in the later films) is introduced in the film’s opening sequence, with voice-over narration explaining how he is a part-Native American Green Beret who has come home from Vietnam and wants to live a peaceful, quiet life away from other people in the forested hills of northern California. Such is not to be his fate, as he comes into contact with the Born Losers, first in stopping them from beating a motorist to death, for which he is sentenced to a prison term, and then in protecting a young college student, Vicky Barrington (Elizabeth James), who is one of the gang’s rape victims. As a cannily produced exploitation film, The Born Losers fulfills all the blunt points of the genre—surly villains, lots of young women in bikinis, plenty of fight scenes—yet the mark of Laughlin’s idealism and sense of social justice creeps repeatedly (and sometimes awkwardly and sometimes contradictorily) into the plot. Much of the story hinges on a trio of college girls who are raped by the sadistic gang members, but then refuse to testify in court because the gang threatens them. The constant presence and threat of sexual violence has an unseemly quality, especially because Laughlin (directing under the pseudonym T.C. Frank) frequently objectifies the victims with his camera, at one point having one of them perform a narratively pointless striptease in her living room before being surrounded by the biker gang again. We might chalk some of this up to Laughlin’s recognition that he is working within the realm of low-budget exploitation and he was likely under direction from American International Pictures, which produced and distributed the film, to give the drive-in audience the skin and sleaze they clearly desired, but even then the sordidness of the film’s tone contradicts Laughlin’s clear intent to emphasize victimization. In this regard, Vicky plays an important role in articulating the horrors of her ordeal, but Elizabeth James is not a particularly accomplished actress, and many of her lines roll off with a kind of detached sarcasm that hinders the drama. There is also the uneasy suggestion that some of the girls sought out and even enjoyed their sexual assault as a kind of rebellion against their parents, one of whom is played by Jane Russell (The Outlaw) in one of her final screen appearances. Laughlin’s desire to give voice to the victims here is earnest, but deeply problematic in the way it plays all too easily into accusations of “they were asking for it.” Laughlin had previously directed two earnest dramas, The Young Sinner (1961) and The Proper Time (1962), so he had some experience behind the camera. Although his work often feels amateurish, at times he gives the The Born Losers an impressive sense of compositional style, and he handles the fight scenes with quick-cut muscularity (while Billy Jack delivers some karate chops, his mastery of Hapkido would not be fully evident until the 1971 film). The same year that Arthur Penn mainstreamed the use of slow motion to heighten the affective experience of brutal death in Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Laughlin similarly turned a gunshot between the eyes into a galvanizing portrait of sudden death extended in time. The violence in The Born Losers is certainly intense for its era, with quite a bit of visible bloodshed and bodily damage, making it a key film in the intensification of graphic violence at the end of the 1960s (The Born Losers was a major hit for AIP; in fact, it was its biggest money earner prior to 1979’s The Amityville Horror). The balance Laughlin clearly wants to strike between the popcorn enjoyment of righteous vengeance and the difficulties of true justice is in there somewhere, but it is so buried and muddled that nothing comes through clearly except the exploitation.

Copyright © 2025 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Shout! Factory | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(2.5)

(2.5)

This four-disc set includes The Born Losers (1967), Billy Jack (1971), The Trial of Billy Jack (1974), and Billy Jack Goes to Washington (1977).

This four-disc set includes The Born Losers (1967), Billy Jack (1971), The Trial of Billy Jack (1974), and Billy Jack Goes to Washington (1977).