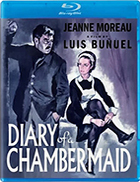

Diary of a Chambermaid (Le Journal d’une femme dechambre)

|  Luis Buñuel’s Diary of a Chambermaid (Le Journal d’une femme dechambre) is not one of his better-known or his best films. But, it is a fascinatingly bizarre minor work, a seemingly straightforward country melodrama that becomes gradually weirder as the story progresses even though the surface of the narrative never quite ruptures in absolute absurdity, as in other Buñuel films. Instead, it stays disarmingly placid, with sickness and twisted ambiguity swirling just underneath. The film is loosely adapted from the turn-of-the-century novel by Octave Mirbeau by Buñuel and Jean-Claude Carrière, who was just beginning his prolific career as a screenwriter, having won an Oscar for Best Short Film the year before with Heureux Anniversaire (1962), which he made with Pierre Étaix (Carrière would go on to work with Buñuel five more times over the next 19 years). The story takes place in France in the late 1920s and concerns Celestine (Jeanne Moreau), a smart Parisian who moves out to the countryside to work as a chambermaid in the manor of a wealthy family that is eccentric, to say the least. The first person Celestine meets is Joseph (Georges Géret), the rather grouchy gardener who has worked for the family for 15 years. We later learn that he is a bigot and a rising fascist who is organizing a right-wing group to spread fascist ideology throughout France. Celestine then meets the lady of the house, Madame Monteil (Françoise Lugagne), a (literally) frigid woman who is materially obsessed with all the objects in the house. Her husband, Monsieur Monteil (Michel Piccoli), a sexually frustrated dolt, spends most of his time out hunting. Celestine was hired, however, primarily to work for Madame Monteil’s aging father, Monsieur Rabour (Jean Ozenne), who seems harmless enough despite his insistent shoe fetish. For the first hour or so, Buñuel appears to be content to let the story play out as a lightly comical farce about the bourgeoisie’s odd combination of shallowness and eccentricity, a theme that obsessed much of his later work. Money makes one weird, he seems to be saying, and Celestine acts largely as a viewer surrogate, thrust into these bizarre surroundings and forced to “settle in” as best she can, which involves her constantly having to deal with sexual advances from all the men, especially Monteil. She gamely puts up with Monsieur Rabour’s requests that she wear a special pair of boots while in his office, and she allows him to touch her calf while she reads to him, but her bored glances and yawning lets us know how uninvolved she really is. The story takes a nasty turn midway, however, when a young girl is brutally raped and murdered in the forest near the Monteils’ estate. Celestine becomes determined to pin the crime on Joseph, who she thinks is a sick, cruel man. In typical Buñuel fashion, however, Celestine does not go about this as one might expect, as she engages him in an ambiguous romantic dance. She plays up to Joseph’s desires, agreeing to marry him if only he will confess to the crime that she is sure he committed. This leads to the film’s most blackly comedic line: As Celestine and Joseph climb into a bed together to make love, the camera discreetly pulls away and we hear her say, “And now, my dear Joseph, tell me you killed little Claire,” as if it is dirty-talk foreplay. Diary of a Chambermaid is a strange work, to be sure, although it is not entirely satisfying. It feels as though Buñuel is playing the line between his surrealist tendencies and straightforward melodrama, giving us a bit of both, but not enough of either. This was one of his more expensive films—shot in anamorphic Franscope widescreen, with beautiful mis-en-scene and gorgeous black-and-white photography,—and the added expense seems to have blurred his sensibilities. There are flashes of dark, malevolent brilliance, such as the disturbing scene in which Celestine witnesses Joseph slaughtering a goose in particularly cruel fashion, forcing it to suffer because, as he says, “They’re better when they suffer, and I like it that way,” which establishes his violent and sadistic personality and makes the later seduction scenes between him and Celestine that much more unnerving. The shot that moves through the black trees and discovers the dead little girl is also masterfully evocative and disturbing, as it discretely shows only her bloody legs covered with large snails she had been collecting—a grisly, but strangely beautiful image. As in most of his film, Buñuel’s political ideology is clearly demarcated, this time in the subplot involving Joseph’s fascist organization. The backdrop of French fascism gives the entire film an uneasy quality that sometimes makes it hard to laugh even when it’s funny—which was surely Buñuel’s intention. Having suffered through extreme right-wing persecution during his formative years as an artist, his political sensibilities stayed strong until the end of his life. The ending of the film is vague in the exact details, but it clearly shows us that all does not turn out well. Buñuel’s cynicism about life and misanthropy toward his characters is on full display here, as the young girl’s rape and murder goes unpunished, Joseph fulfills his dream of running a restaurant in a nearby town, the fascists march proudly through the city streets, and Celestine marries the Monteils’ neighbor, a retired military man, and becomes yet another member of the bourgeoisie. It is this last bit that is the real kicker because we realize that, despite Celestine’s seeming passivity for most of the film, having a chambermaid of her own is what she really wanted all along.

Copyright © 2025 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Kino Lorber | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overall Rating:

(3)

(3)