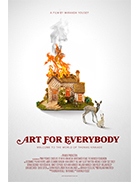

Art for Everybody

|  Whether you love or loathe his work, there is no question that Thomas Kinkade, the trademarked “Painter of Light,” was an immensely talented artist. Even if you chafe at the idea of his hypersaturated, idealized cottage paintings set against luminous backdrops of setting suns and glistening snow and purple mountains, there is no denying the enormity of the skill that was involved in creating those images—the nuanced details, the organization of space, and, of course, the evocation of a resplendent light that transcends reality and enters into some kind of ethereal sublime. For some it is heavenly, for others it is hellish, but it is clearly the product of a gifted hand. Kinkade is the subject of Miranda Yousef’s intriguing, absorbing, and genuinely (no pun intended) illuminating new feature documentary Art for Everybody, the title of which derives from a New Yorker essay written by Susan Orlean in 2001 during the height of Kinkade’s popularity. Like most serious artists and writers, Orlean was suspicious of Kinkade’s mega-success, not only because of the kitschy, aggressively soothing nature of his paintings, but the manner in which they were reproduced and mass-marketed via television shopping channels, mail-order catalogs, and single-artist galleries that were sprinkled throughout malls and high-end shopping districts all throughout the U.S. Kinkade’s romanticized landscape paintings were the core of a multi-million-dollar business in which his art was emblazoned on everything from blankets, to pillows, to coffee mugs, to collector plates. His paintings were reproduced on an industrial scale, but often given the illusion of uniqueness by having artists apply a few dabs of actual paint to the prints. Kinkade’s talent was real, but what ostracized him from the serious art world was the way he so completely and unironically monetized it while also presenting himself as a gleaming bastion of home, family, and conservative Christian values. Yousef, who has worked primarily as an editor on documentaries and television series for the past 15 years, gained unprecedented access to Kinkade’s family and business associates, which allows her to construct a challenging portrait of a complex man who played many roles throughout his life and may have never really known who he was even as he felt sure about who he needed to be. Kinkade, who died in 2012, appears throughout the film in photographs and extensive video footage, much of which comes from home movies shot by his family members, thus offering an intimate glimpse into his private life. This is often contrasted with the thousands of public appearances he made on television, both hawking his wares on QVC and demonstrating his painting techniques on various programs. His public persona—a big, cuddly man with a bushy moustache and a broad smile—matched the lure of his paintings, making him the complete package. Of course, as interviews with his ex-wife Nanette (to whom he was married most of his adult life), his four adult daughters Chandler, Everett, Merritt, and Winsor, and his various business partners (Dan Byrne, Ken Raasch, and Linda Raasch) attest, that package was far from perfect and constantly straining and cracking under the weight of its expectations. And that is what makes Art for Everybody such a complex, moving tragedy. Yousef skillfully builds the trajectory of Kinkade’s life, following him from a bohemian art student trying to find his voice, to the rapidly escalating success of his cottage paintings and the massive, ambitious business he built out of them, to his slow collapse via bad fiscal practices, overexposure, lawsuits, and alcoholism that wrecked him personally and professionally. The intimate nature of the interviews with those who knew and loved him (including his brother, Patrick) is balanced by a wider view proffered by artists and critics who attempt to explain (or explain away) his previously unimaginable success. Christopher Knight, the art critic for the Los Angeles Times, is the most conventionally condescending in his complete dismissal of Kinkade’s work, although others defend him, including maverick animator and painter Ralph Bakshi, who first hired Kinkade to paint backgrounds for his 1983 animated sword-and-sorcery film Fire and Ice; Jeffrey Valance, an artist who curated Kinkade’s first art-world exhibition at CalState Fullerton’s Grand Central Art Center; and avid collector and dealer Karen de la Carriére. The film’s biggest revelation, though, is the dark, surreal, and provocative paintings and sketches that Kinkade hid from the rest of the world in a locked, closet-sized vault inside his house. Constantly hinted at throughout the film by slow tracking shots into a massive lock on the heavyset door, this art is eventually revealed by two of Kinkade’s daughters, who sift through it and talk about what it means to them and what they think it reveals of their father. Much of the work was done early in Kinkade’s life (some dating back to when he was in middle school) when he was still trying to find himself as an artist, but much of it is contemporaneous with his cottage paintings, suggesting a multifaceted man who felt compelled to reveal only one aspect of his artistry to the world. The documentary culminates with many of the interview subjects being show this darker, previously unseen work, and the look of astonishment on their faces provides a stark reminder of how difficult it is to truly know an artist, even one as widely disseminated as Thomas Kinkade. Copyright © 2025 James Kendrick Thoughts? E-mail James Kendrick All images copyright © Tremolo Productions |

Overall Rating:

(3.5)

(3.5)